37 min to read

A Grave Threat To Mental Health

Languishing occurs because we fail to allocate our attention into a continuously immersive experience.

This is the full text from chapter 3 of my book.

The following chapter integrates central ideas from various thinkers. I am not reinventing, but instead synthesizing their ideas. I want to carefully simplify and demystify the process that threatens our collective mental health. Our mental health declines once our psychological needs (competence, autonomy, and relatedness) are disrupted. However, once these needs are met, then we become self-determined (Deci & Ryan, 1985).

Disruption #1: Task Switching

A task is an assigned piece of work that is expected to be done. Focusing too much on what has to be done is being outcome-oriented which leads to languishing. This ties into the tantalizing pursuit for knowledge because as we learn more, then we develop ideas for what we don’t know. In this process of obtaining more knowledge, we can generate more ideas for getting what we want. In the short term it’s quick but in the long term it isn’t effective for our mental health. We languish from this overwhelming feeling of being unable to halt this pursuit where the cost of remaining comfortably sedentary is unbearable. Languishing is purgatory between flourishing and depression. Languishing occurs because we fail to allocate our attention into a continuously immersive experience. Perpetual task switching disrupts immersion. Cal Newport captured perpetual task switching in his idea of the ‘hyperactive hivemind’ for modern work. Essentially, this is the idea that we are constantly task switching to accommodate for our reception of instantaneous notifications. He argues that there is no longer structure in the digital world, and I think its unpredictability is haunting us and coercing us into a state of languishing. Structures become shackles. Languishing is not about control; it’s about how we influence outcomes. By reading this treatise, you should see that we cannot control outcomes. In languishing, we influence outcomes but in the wrong ways. Maybe now, in contemporary times, we have such terrible ways of influencing our outcomes that they render our autonomy as obsolete. For example, dreaded modern emails will bombard your inbox—that is just an uncontrollable outcome. Yet what you can control is how you influence that outcome. Let’s suppose there are two influential choices:

- Answering emails immediately as their notifications ping in

- Batch answer emails once a day and deal with them in bulk

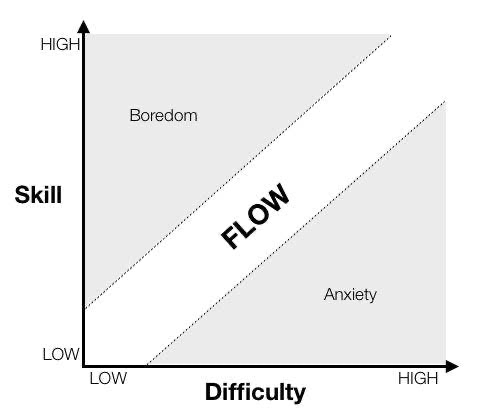

The first route doesn’t seem to make much sense because it would distract us from our present task each time that we get a ping. However, that’s the route we often choose because we want to immediately respond to our thoughts of who sent the email, its contents, etc. We have to task switch here because the longer we attempt to ignore responding, it solicits the rest of our attention until we open the email. Psychologically speaking, when we task switch, there is attentional residue. We cannot control when emails arrive, but we can control when and how to respond to them; this is how we influence them. In the same vein, I’m assuming we don’t fold one article of laundry then begin doing something else. Instead, we fold all of the clothes then we do something else. Thus, a better way of influencing outcomes is to not task switch. From what I know, flow state happens when you have enough competence in something and feel immersed in that something. Attentional residue from constantly task switching aggravates our immersive experience in flow state. Folding clothes is neither easy nor hard; it’s just the right level of competence. We can get in the flow of folding laundry, but not if we task switch after folding only one piece of clothing because the immersion is lost. We have to sustain that folding of laundry if we want to achieve that flow.

Task switching interrupts that flow. It creates a discontinuity in our attention. We shift too quickly from one outcome to the next outcome. This ties into that telic thinking and being too goal oriented. Once you get that notification ping and see that it is from Gmail, then you become telic in your thinking and your brain now has the additional task or objective of checking that email regardless of your objective before the notification came in. Turn notifications off so you don’t have to worry about it. It makes sense that the aphorism out of sight out of mind is true. As a consequence of more knowledge, you also have more opportunity to task switch. Since you know something exists, you can think about it. Bo Burnham poignantly observed that unlimited access to everything and anything all of the time has made apathy a tragedy and boredom a crime. I am sure you have had a shocking thought and that you can’t get out of your head. Let’s imagine we are at a busy intersection and there is a sweet helpless old lady to our side. Any swift jab could knock her fragile being into the roaring traffic. We know that we would never do this, so why are we now fixated on this idea of pushing an old lady into traffic? Well, by setting this objective, our brain constantly measures how far away we are from reaching the objective even if we want to get away from the objective. In bad cases, this can lead to obsession. In good cases, we can use this to our advantage in the case of paradoxical intention aka reverse psychology. We can use flow state as a means of engagement to keep languishing at bay. I think this statement is the perfect distilled essence for approaching self-determination. We have kept task switching especially during the pandemic which is problematic if we want to be self-determined. We have let outcomes control us rather than us influencing the outcomes. To end languishing, try starting with small wins. These small wins force us to micromanage ourselves and focus on achieving small bouts of flow. Languishing is not merely in our heads it’s in our circumstances. And more importantly I think, is how we influence and perceive these circumstances. Outcomes are inevitable and thus avoidance strategies would be futile. In order to achieve that flourishing, we need to increase engagement strategies towards those outcomes. Not being outcome oriented and not having goals is not an option. No matter what, you will always be teleologically measuring against an outcome. Not having goals is itself a goal. In teleology Aristotle had made the distinction between telic and atelic activities. Telic activities serve some instrumental means to an end which will seduce us to the hedonic treadmill. In contrast, atelic activities are in and of themselves; they are performed for their own sake, not in order to achieve a particular end. For instance, you do hobbies because you like it. The activity is its own reward. You are not aiming for expertise; You are aiming for fulfillment.

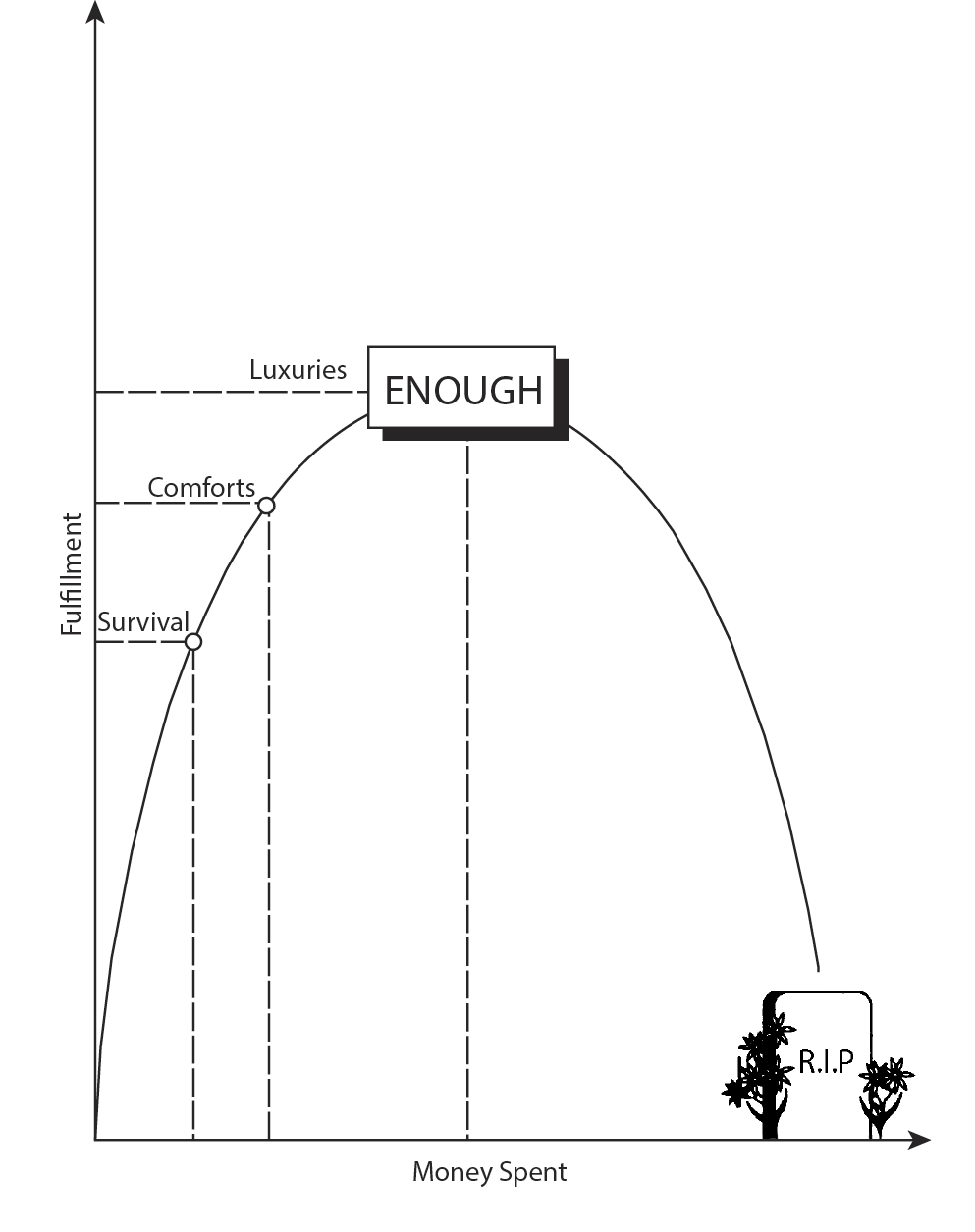

Do not believe that money = fulfillment. Remain at the peak of the curve: ENOUGH. It is fully appreciating and enjoying what money brings into your life and never purchasing anything that isn’t needed and wanted. A wise man can make use of whatever comes his way, but it is in want of nothing. On the other hand, nothing is needed by the fool for he does not understand how to use anything but he is in want of everything i.e. upekhha.

With so much knowledge and susceptibility to compare against others, we are mistaken to get caught up in telic activities. to be happy, an atelic perspective is the goal. This is one of the central tenets of Stoicism: Learn to enjoy the things that you are doing, no matter your circumstances because you cannot control circumstances. Approach circumstances sincerely and not seriously, that way, you will find more enjoyment. Productivity is more about enjoying the journey than it is about getting more things done aka optimization. Be careful not to fall into the trap where enjoyable things like vacations become something to get done, rather than something to enjoy. The price of higher productivity is always lower creativity. When we enjoy what we’re doing and we’re competent enough, we can get immersed in flow state and use that as a means of engagement. Eventually we achieve self-determination. All of these things shouldn’t require motivation if it is intrinsic. Nobody needs willpower not to eat a chocolate bar when there isn’t one around. And nobody needs willpower to do something they wanted to do anyway. We should only need motivation for dealing with short term pain because we fail to recognize that we must bear present frustrations in the interests of longer purposes (failure to do so is the idea of delay discounting). We are creatures that thrive on instant gratification, but it is our logic and rational thinking that permits us to plan ahead. The desire for instantaneous feedback seduces us onto a path of languishing because we constantly task switch from one outcome to the next. Don’t practice what you don’t want to become.

Disruption #2: Additive Solutions

To make matters worse, we unintentionally add more things on our plates which catalyze languishing by disrupting immersion. Busyness is a recently lauded phenomenon that goes hand-in-hand with hustle culture. People think they’re making a living when, in fact, they’re making a dying. Karoshi means death by overwork. In explaining busyness: “Here we show that people systematically default to searching for additive transformations, and consequently overlook subtractive transformations.” Our usual preference is to let live what lives: we would choose to keep all the functionality if we could. The reason participants in the study offered so few subtractive solutions are not because they didn’t recognize the value of those solutions, but because they failed to consider them. Thus, it seems that people are prone to apply a ‘what can we add here?’ heuristic. This heuristic can be overcome by exerting extra cognitive effort to consider other, less-intuitive solutions. But, why the biased heuristic to begin with? Subtractive solutions are less likely to be appreciated. People might expect to receive less credit for subtractive solutions than for additive ones. A proposal to get rid of something might feel less creative than would coming up with something new to add, and it could also have negative social or political consequences — suggesting that an academic department be disbanded might not be appreciated by those who work in it, for instance. People could assume that existing features are there for a reason, and so looking for additions would be more effective. Sunk-cost bias and waste aversion could lead people to shy away from removing existing features, particularly if those features took effort to create in the first place. “We all face distractions from the deeper efforts we know are important: the confrontation of something not going right in our lives; an important idea that needs development; more time with those who matter most. But we delay and divert. It’s easier to yell at someone for doing something wrong than to yell in pride about something we did right. It’s easier to seek amusement than to pursue something moving. When presented with a challenging scenario, humans cannot evaluate every possible solution, so we instead deploy heuristics to prune this search space down to a much smaller number of promising candidates. As this paper demonstrates, when engaged in this pruning, we’re biased toward solutions that add components instead of those that subtract them” (Cal Newport). “Defaulting to searches for additive changes may be one reason that people struggle to mitigate overburdened schedules, institutional red tape, and damaging effects on the planet.” “As I read about this finding, I couldn’t help but also think about the epidemic of chronic overload that currently afflicts so many knowledge workers. The volume of obligations on our proverbial plates — vague projects, off-hand promises, quick calls and small tasks — continues to increase at an alarming rate. There was a time, not that long ago, when the standard response to the query, ‘How are you?’, was an innocuous ‘fine’; today, it’s rare to encounter someone who doesn’t instead respond with a weary ‘busy.’” (Cal Newport). Adding more things includes distractions too. When, in fact, LESS IS MORE. Following Occam’s razor, (law of parsimony), no more assumptions should be made than are necessary in explaining a thing. The principle is often invoked to defend reductionism or nominalism. Morgan’s canon is an equivalent adaptation for explaining animal psychology: never attribute a behavior to a more complex mental event if a simpler one can do (see the story of Clever Hans). “Until we have begun to go without them, we fail to realize how unnecessary many things are. We’ve been using them not because we needed them but because we had them.” “This is a particular problem of our age. We aimlessly watch YouTube videos or scroll our Twitter feeds for no reason other than that we can. If we didn’t have the ability to engage in such automated behaviors, our lives would not be any poorer (and would in fact be much richer).” Do as little as needed, not as much as possible. We’re unhappy because we’re insatiable. After working hard to get what we want, we lose interest in the object of our desire. Rather than feeling satisfied, we feel a bit bored, and in response to this boredom, we go on to form new, even grander desires. The easiest way to gain happiness is to want the things you already have. You are living the dream you once had for yourself. Think about the positions of your ancestors: unfortunately, they will never have the experience of getting to live with the modern pleasures that you have. “Human life is gradually turning from a struggle against starvation into a struggle against addiction. We’re constantly being pampered with new comforts and conveniences, and before we can begin to appreciate one we’re offered another.” “If we focus on rediscovering and re-enjoying what we’ve begun to take for granted—the simple, essential things like our health, homes, and loved ones—then we fill the void in our hearts that would otherwise lead us to endlessly chase dopamine hits.” Being selective in choosing the objects in your life is key. “Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away” (Antoine de Saint-Exupéry). “Continuous improvement is better than delayed perfection” (Mark Twain). Perfection is procrastination masquerading as quality control. Every action you take is a vote for the kind of person you’ll be in the future. If you do a thing today, it’s more likely you’ll do it tomorrow.

Disruption #3: Outsourcing Processes

Given our tasks, I have mentioned two ways in which they disrupt immersion: task switching and adding too many tasks. Now, when we have multiple task processes to attend to, then we might decide to outsource those processes. Yet, in doing so, you obviously can no longer be immersed in those processes anymore; you are abandoning the development of values. Clayton Christensen has warned about the dangers of outsourcing processes. “When I let go of what I am, I become what I might be” (Lao Tzu). For example, thinking is a task we often outsource. When you choose ‘what to think’ instead of ‘how to think,’ you are outsourcing processes; specifically, the process of thinking. Allow me to make the distinction between ‘what to think’ and ‘how to think.’ Recently, I’ve been overhauling my tools that help me ‘how to think.’ I’ve been afforded the time this summer [2020] to really adjust my perceptions of the world. Let’s take a knife for example: When you hone the knife regularly, you’ll have to sharpen it less often. I’ve been honing my tools regularly so that I have to sharpen them less often. Okay, enough with the knife metaphor, what do I really mean here. Well, ‘what to think’ is leveled thought and ‘how to think’ is layered thought. Leveled means you sequentially process components whereas layered means that you can simultaneously process components at once. Levels: Thoughts are serial like the runners passing off a baton in a relay race. This is serial processing. Layered: Thoughts are paralleled like the runners leaving at the same time but can go in different places. This is parallel processing. One way I’m learning to become more layered in my thoughts is by diversifying my identity. I’ve been avoiding thoughts that pertain only to myself. This will lead to passionate decision making that only serves to satiate the ego. Instead, I’ve been loitering more with thoughts that pertain to the collective. This has led me to make decisions that are beyond myself and serve a purpose. In other words, passion serves yourself and purpose serves beyond yourself. People like to simplify people in order to make sense of things in their own head, the tribe around you reinforces your brand by putting you in a clearly-labeled, oversimplified box. For example, instead of thinking “I have to do something” I think “I get to do something.” Given my current circumstances, I am afforded the opportunity to get to do this something. This line of thought has helped me to become more layered and think beyond my own self. It sets a frame of perspective that discourages thinking in levels or ‘what to think.’ I used to think in levels of happiness. You have an idea of an outcome (happiness) but have no idea of means in which to achieve such an outcome. I knew ‘what to think’ about happiness but I didn’t know ‘how to think’ about happiness. So, I was determined to learn ‘how to think’ about happiness. Depression might serve as a response to ‘super-stimuli’? Super-stimuli made many processes obsolete? Tradition is a set of solutions for which we have forgotten the problems. Take the solution away and often the problem comes back. By losing processes, we are losing fulfillment/purpose and consequently happiness/meaning? Let’s use a phone as a metaphor. I’m presuming you have no idea how the phone operates from a layered frame of thought. However, from a leveled frame of thought, you probably know how the phone operates: you tap a few times and you’re calling someone. A layered frame of thought would consist of knowing the minutiae of technology that gives rise to the phone as we know it. But how exactly does that calling work? What are the buttons doing to communicate to the phone what I want it to do? In technology, APIs are bridges over the layers and onto the outcomes. If we had the time to actually care enough to understand how the phone actually ‘thinks’ we’d probably be much more appreciative of it. This is exactly the point about ‘how to think’: it’s time consuming. ‘What to think’ is so much easier! You can jump to conclusions quicker because you take a one-way shortcut route. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts, but the whole wouldn’t exist without its parts summed. The whole is often an emergent property. Prevention {of disease] usually requires lifestyle changes. This is harder to sell and implement. Many people prefer taking a pill over changing their diet. Treatment is easier and more profitable. And so the system is built around that. You would think that going to school is about learning and acquiring skills, but then why do students pay tens of thousands of dollars for Ivy League schools when all of the learning material is effectively available online for free? Why do we use grading systems when we know that students learn worse when being graded? The answer, again, is signaling: Education helps with credentialing and signaling to potential employers. Employers have not the time to inquire about this process and journey of self-disciplined education. Instead, they want to see ‘Harvard’ on a resume from the person, hire that person on the spot, and call it a ‘satisfice’tory day. Yeah, this choice is a heuristic that works pretty much most of the time (on resume prestige paper), but it is sincerely unfair to the genuinely academically-driven student: I suppose such is a pessimistic outcome of life. “For centuries, elite academic institutions like Oxford and Harvard have been training their students to win arguments but not to discern truth, and in so doing, they’ve created a class of people highly skilled at motivated reasoning. The master-debaters that emerge from these institutions go on to become tomorrow’s elites—politicians, entertainers, and intellectuals”… “Master-debaters are naturally drawn to areas where arguing well is more important than being correct—law, politics, media, and academia—and in these industries of pure theory, secluded from the real world, they use their powerful rhetorical skills to convince each other of fashionably irrational beliefs (e.g. wokeism). During their master-debatery circlejerks, the most fashionable delusions gradually spread from individuals to departments to institutions to societies.” … “Naturally, woke intellectuals don’t consider themselves alarmists or conspiracy theorists; they believe their intelligence gives them the unique ability to glimpse a hidden world of prejudices. What they don’t know is that high IQ people and low IQ people display similar levels of prejudice, except toward different groups, and educated people actually display greater prejudice against those with different views” … “Despite being irrational, wokeism is nevertheless an intelligent worldview. It’s intelligent but not rational because its goal is not objective truth but social signaling, and in pursuing this goal it’s a powerful strategy. People who engage in woke rituals, such as proclaiming their pronouns during introductions, or capitalizing the word ‘black’ but not the word ‘white,’ signal to others that they’re clued-up, cosmopolitan, and compassionate toward society’s designated downtrodden. This makes them seem trustworthy and likable, and explains why wokeism is most prevalent in industries where status games and image are most important: media, academia, entertainment, and corporate advertising.” (Gurwinder Bhogul, Why Smart People Hold Stupid Beliefs). “That is exactly what places like Yale mean when they talk about training leaders. Educating people who make a big name for themselves in the world, people with impressive titles, people the university can brag about. People who make it to the top. People who can climb the greasy pole of whatever hierarchy they decide to attach themselves to” (William Deresiewicz, The American Scholar, Solitude and Leadership). “But when you don’t know how to reason, you don’t know how to evolve or adapt. If the dogma you grew up with isn’t working for you, you can reject it, but as a reasoning amateur, going it alone usually ends with you finding another dogma lifeboat to jump onto—another rule book to follow and another authority to obey. You don’t know how to code your own software, so you install someone else’s” (Tim Urban, The Cook and the Chef). For example, someone says: “Our president is a buffoon!” Well. Okay. Sure. You may be right, but are you effective in conveying your thought? No, you’re not effective because you are telling me ‘what to think,’ not ‘how to think.’ You are merely telling me the outcome without providing me how you got there. Of course, don’t solicit how you got there unless someone asks. People might not care enough to hear beyond the buffoon part; they could simply be satisfied by hearing the outcome. That’s completely fine! We don’t have to understand the layers because our beautiful liberties permit us the choice! However, if you’re curious, a better approach to conveying that statement could be: “Our president unconditionally accepts plaudits, yet vehemently dismisses antagonistic criticism as demonstrated by X, Y, and Z.” Of course, we’ve never witnessed that sort of statement. Reasonably so. We’ve presumably taken a long time to arrive at our outcome and want to just quickly state our outcome because people have neither the time nor care to hear how you arrived at that outcome. To avoid the labor of ‘how to think,’ we leave the layers to the experts. Going back to our example with happiness, nobody has made a proper invention that takes the layers out of happiness. There is no simple ‘phone metaphor’ equivalent for happiness: Money? Sex? Drugs? Those routes are all leveled approaches to thinking about happiness. ‘What to think’ about happiness will not help you; you are only thinking about the outcome. In contrast, ‘how to think’ about happiness will help you to understand how to approach that outcome. Thinking in layers provides you with the many paths that lead you towards your intended destination. There’s an impasse along one path? Okay, that’s fine. Take the other path or the other path. You also begin cultivating complex associations between paths. “I’d fallen into one of the oldest process trap of all: I had cargo culted methods whose principles, concepts, and motivations I did not understand. I had copied the ritual without understanding the mechanism” (Baldur Bjarnason, The Different Kinds of Notes). “A child’s instinct isn’t just to know what to do and not to do, she wants to understand the rules of her environment. And to understand something, you have to have a sense of how that thing was built. When parents and teachers tell a kid to do XYZ and to simply obey, it’s like installing a piece of already-designed software in the kid’s head. When kids ask Why? and then Why? and then Why?, they’re trying to deconstruct that software to see how it was built—to get down to the first principles underneath so they can weigh how much they should actually care about what the adults seem so insistent upon” … “But it might be a nightmare worth enduring. A command or a lesson or a word of wisdom that comes without any insight into the steps of logic it was built upon is feeding a kid a fish instead of teaching them to reason. And when that’s the way we’re brought up, we end up with a bucket of fish and no rod—a piece of installed software that we’ve learned how to use, but no ability to code anything ourselves” (Tim Urban, The Cook and the Chef). I’m hoping I’ve sparked some curiosity in you so that you begin caring enough to understand ‘how to think’ and not ‘what to think.’ Think for yourself, don’t let others think for you. You have your own unique experiences. How does your journey towards the outcome change when you learn ‘how to think?’ Seneca the Younger once suggested that sometimes we are the worst obstacles to our own improvement. We may be the obstacles because we are only thinking about ourselves. Start learning ‘how to think’ by beginning the construction of your layered thinking. The fact that a layer’s protocol both constrains and deconstrains a system is crucial. It delineates optimal choices for specific scenarios. Constraints give your life shape. Remove them and most people have no idea what to do: look at what happens to those who win lotteries or inherit money. Take the time to examine your thoughts in order for you to live better. Investing time in yourself is always a worthy investment. In addition to thinking, we have also outsourced many of our cultural values. Now we are riding the inertia of old values. The momentum of capitalism and democracy are riding on old cultural values based on religion. Business is the most important way in which human beings cooperate. In his Philosophical Letters, Voltaire understood that if diverse people are to cooperate, they must focus on their common interest and leave other predilections, like religion, at home. Unfortunately, the woke movement is bringing religion along with every other aspect of life back into business. These days, corporations that don’t go woke are forced to go broke. Wokeism is “a popularized academic worldview that’s half conspiracy theory and half moral panic. Wokeism seeks to portray racism, sexism, and transphobia as endemic to Western society, and to scapegoat these forms of discrimination on white people generally and straight white men specifically, who are believed to be secretly trying to enforce such bigotries to maintain their place at the top of a social hierarchy” (Gurwinder Bhogul, Why Smart People Hold Stupid Beliefs). People develop an identity around a label and become a victim to opposition. The religions have changed, but Voltaire would not have been surprised at the consequences: a breakdown of cooperation and amity (Tyler Cowan). Remaining mission-focused sustains cooperation among diverse groups of people, operating at a high level of performance. As a result of abandoning being mission-focused, and adopting wokeness, the woke movement has led to the cancellation of many people. This is because we now have certain people policing values that no longer come instinctually to us. Values came to us instinctually from instilled religion, but we have abandoned religion and outsource our values from elsewhere. When there is no common bond, we cannot know how to work separately as a means of working together. The world seems to be losing its mind. No one is sure what the rules for acceptable conduct are any more. From virtue signaling to moral grandstanding, the incentives to take down others are stronger than ever. The opposite of a beginner’s mind is the jaded sensation that “you already know it”. It is the implicit competing commitment that if you don’t signal your expertise to the people around you, you lose your identity because your intellectual accomplishments define you as an individual. This may be a cognitive distortion. Self-worth theory is the tendency of some students to associate their human value with their school grades. When you leave school, you may tie such a tendency to your work, or the money you earn. Your ego—the force of resistance against a beginner’s mind (shoshin)—gets in the way. The middle way of life is something I think of as Committed & Unattached: Committed: You are fully committed to the goal. You work at it as if it were one of the most important things in the world. You give it your all (within the bounds of self-care, of course). You focus, you go after it. You care deeply. Unattached: But while you’re committed to making it happen, you are unattached to the outcome. You care about the outcome but you’re OK if it doesn’t happen. You love life and yourself no matter what happens. Think of it like really taking care of a seedling, and then the sapling that grows from it, then the tree, with your full devotion — but then not needing the fruits that might or might not spring from the tree. This is one of the key lessons from the sacred text, the Bhagavad Gita — to give yourself with full devotion to your life’s purpose, but then to “let go of the fruits.” Auftragstaktik: (mission command in US & UK): military tactic where the emphasis is on the outcome of the mission rather than the specific means of achieving it. Allows flexibility in the field. Devising plans that consider the circumstances that are encountered—not those expected to encounter because expectations can bias judgment. In more complex situations, principle stacks are ideal, in other words identify your priority or goals, then rank them in order of importance. That way, there is a navigable framework for handling tricky decisions without imposing strict boundaries. Soldier versus scout mindset. Puzzles don’t come already put together in the box, but they still make beautiful pictures in the end.

Simone Smerilli: When in the process of making a decision, seeking more information has diminishing returns. Diminishing returns means that the more information you seek, the less valuable it becomes. For most decisions in life and business, the amount of variables and information at play is too large for us to factor in our decision-making ‘equation’. There are factors we don’t know we don’t know. So, we satisfice when making decisions. We pick the best option based on our current resources and the information available. We know, if we look within, that there are tradeoffs we make and heuristics we employ in order to make the decision. And we need to be okay with that, because getting all of the information needed may turn into a life-long endeavor in itself. Sometimes, decision-making is also constrained by time—say, for a military commander during a battle, or the executive board during a cyber security attack on the company. That can be bad and good. It can be bad because when there is a time constraint and the decision is high-stakes, you risk letting emotions take over and make the first decision that comes to mind, driven by your sense of panic. It can be good because of Parkinson’s Law: work expands to fill the time allocated to it. If you manage to establish order in the process of decision-making under time constraints, you may optimize your satisfice decision, picking the best choice you can given the circumstances.” People tend to be satisficers: they stop information seeking after finding information that is good enough, given the time constraints in specific situations. And when enough information is gathered for you to make up your mind with a high degree of confidence, it is time to embrace your choice fully. Especially in time-constrained situations, there is no space for haphazardly moving forward; decisive commitment is required at all levels. Everyone involved in the action (e.g., your military army, your employees) needs to be informed of the vision and their role in it with the utmost clarity. This is what general Stanley McChrystal also points out in a conversation on the Knowledge Project podcast. And there is also the aftermath of decision-making. A decision doesn’t stop when you make the decision. A decision continues until the situation for which you are deciding ends. That’s because as you commit to the decision and move along the action curve, you get feedback on your decision. And feedback empowers you to adjust your course of action. You can incorporate feedback into your mental model of decision-making and course correct along the way with the highest level of humility and receptivity possible. Because you don’t even know what you don’t know, many times. What you see is all there is, as Daniel Kahneman puts it in Thinking, Fast and Slow. Seeking more information before making a decision has diminishing returns. Being highly receptive to feedback during execution and adjusting your position along the way can have positive compound effects (or negative ones, if you confuse noise with signal).

“Diogenes of Babylon was certainly crafty and had a mind well suited to politics. Cicero tells us about a debate he had with his student Antipater over the ethics of selling a piece of land or a shipment of grain.” “But Diogenes argued that nothing would ever sell if every fact was disclosed. How could a market work without the pursuit of mutual self-interest?” (Lives of the Stoics, p. 61). For example, we’ve adopted ‘busyness’ as a new value in our culture: people signal busyness because that’s what the world currently values. Additionally, Terror-Management Theory explains the crafting of values that ignore or avoid inevitable death. Robin Hanson suggested that beliefs become entrenched. Belief entrenchment occurs because many traditional institutions are opting to incur marginal costs over adopting better long-term full costs. There’s a tremendous bias against taking risks. Everyone is trying to optimize their ass-covering. The wise of every generation discover the same truths. Tradition is a set of solutions for which we have forgotten the problems. Take the solution away and often the problem comes back. “People are now spending MORE on eating out than groceries. Too lazy to cook, too lazy to learn how to cook. Let’s just ‘outsource’ cooking… …by DRIVING around to eat out… …while our expensive kitchens gather dust… …and so we save time to watch cooking programs on TV. Guess what? You PAY for all that. For years, 90% of the foods I ate were home-cooked. Big savings again.”

(Mehdi, StrongLifts)

In Sum

Languishing threatens our mental health since it’s a state where immersive experiences are disrupted. Disruptions to our immersion: Task switching: Outcomes are inevitable simply because of our responsibilities for accomplishing them and that we are telic-thinking creatures in our evolutionary nature. However, the ways in which you influence them must limit the opportunities for attentional residue. Additive transformations: Adding distractions in the form of more tasks that masquerade the truly important tasks festering underneath. Outsourcing processes: Reflexively adopting leveled perspectives over layered perspectives because of both time and cognitive effort. Simply teleporting to the destination instead of journeying along has made a unified culture of values appear distant and unfamiliar. How can we better serve our future mental health in the long term? One idea that Cal Newport has suggested with regards to modern work is the use of Kanban boards as a means for replacing the hyperactive hivemind since software developers have already successfully adopted this alternative.

I have also come across the concept of complexity, wherein less is more. Complexity brings upon more problems and managements focus on problem-solving and never on problem-finding. For instance, management says workers are using too much blue coat PPE. Well, I use them daily for their functional pockets. Yellow gown PPE is limited in pocket space for equipment: pens, flashlight, phone, and notepad. Problem-finding is more sincere and compassionate. It comes from a place of considerate understanding. Problem-solving can be brutish, ignorant, and negligent of the process. Attention is the most valuable resource you have, one could argue. Attention is what you decide to do with your limited willpower reservoir. There is abundance in the world of attention, and your attention is drained by every activity in which you decide to partake. There is a constant tension between the finitude of existence and the infinity of potential things to do. Time management means coming to terms with that tension, and contemptibly choosing what not to do. Efficiency is not the answer to getting more things done and eradicating your psychological discomfort when facing the gap between what you deem important and what you are actually allocating time to. Efficiency is a trap. When you become more efficient, you increase your level of busyness on unimportant stuff. If you become more efficient at emails, you increase your time spent on emails because now conversations flow almost instantaneously and you get more emails to answer. Missing out is what makes life worth living in the first place. By not doing something, you are choosing to do something else. Possibilities are endless, and your life is finite. Missing out is what makes your life worth living because it lets you accept imperfection. Imperfection is life. When making decisions, you will never have all the information you need, so you are called to satisfice and adjust along the way. That’s the joy of missing out: being happy with the imperfect now instead of craving a utopian perfect future. Making decisions is a commitment to imperfect actions in actuality, as opposed to fantasizing about your perfect future without taking any action in the present. Developing a habit of making decisions, even if we will never have all the information needed, is a component of a great life. Decisions bear consequences. Hence they bear responsibility. That’s part of a well-lived life. Multitasking feels more psychologically comforting than focusing on one single thing. That is one reason why we may multitask. Multitasking is used as a way to escape the pain of being finite, as Oliver Burkeman asserts. This concept reminds me of the difference between strategy and planning (Martin, 2022): strategy is full of assumptions and high risk; planning is linear and has lower risk. In describing situations we attempt to analyze/model/predict the variables in an environment: they are volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous ( VUCA ) Possibly regarding terror-management theory: In truth, this belief may be a by-product of the inescapable finitude and uncertainty of existence, which we all need to face and deal with at some level.